|

Giving and Recieving Feedback2/8/2023

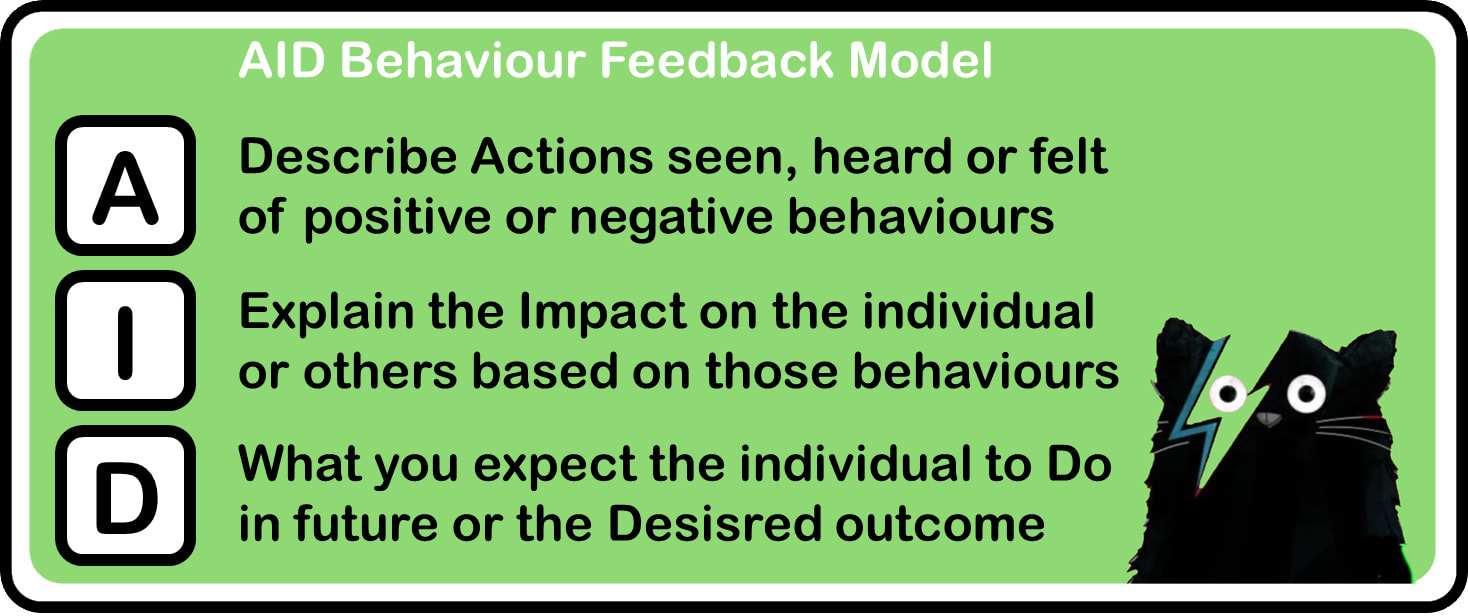

0 Comments Giving and Receiving Feedback Giving and receiving feedback is an essential skill in both personal and professional relationships. Constructive feedback can lead to growth, improved performance, and better relationships when delivered and received effectively. Here, Alec McPhedran gives an overview of approaches to giving and receiving feedback. In life as much as in work, it’s important to know how to provide feedback to others, effectively and constructively without causing offence. Equally, and often less considered, is the ability to seek and receive feedback. There are many opportunities in life for providing others with and for receiving feedback, from commenting on the way that your colleague has carried out a task, to discussing your behaviour with them. This item focuses on the process of communicating with someone about something that they have done or said, with a view to changing or encouraging that behaviour. This is often called ‘giving feedback’, and when you do, you want your feedback to be effective. 'Feedback' is a frequently used term in communication theory. It is worth noting that this page is not about what might loosely be called ‘encouragement feedback’—the ‘yes I’m listening’-type nods and ‘uh-huhs’ which you use to tell someone that you are listening. What is Effective Feedback? For our purposes, we will define effective feedback as that which is clearly heard, understood and accepted. Those are the areas that are within your power. You have no control over whether the recipient chooses to act upon your feedback, so let’s put that to one side. So how can you make sure that your feedback is effective? Develop your feedback skills by using these few rules, and you’ll soon find that you’re much more effective. 1. Feedback should be about behaviour not personality The first, and probably the most important rule of feedback is to remember that you are making no comment on what type of person they are, or what they believe or value. You are only commenting on how they behaved. Do not be tempted to discuss aspects of personality, intelligence or anything else. Only behaviour. 2. Feedback should describe the effect of the person’s behaviour on you After all, you do not know the effect on anyone or anything else. You only know how it made you feel or what you thought. Presenting feedback as your opinion makes it much easier for the recipient to hear and accept it, even if you are giving negative feedback. After all, they have no control over how you felt, any more than you have any control over their intention. This approach is a blame-free one, which is therefore much more acceptable. Choose your feedback language carefully. Useful phrases for giving feedback include: “When you did [x], I felt [y].” “I noticed that when you said [x], it made me feel [y].” “I really liked the way that you did [x] and particularly [y] about it.” “It made me feel really [x] to hear you say [y] in that way.” 3. Feedback should be as specific as possible Especially when things are not going well, we all know that it’s tempting to start from the point of view of ‘everything you do is rubbish’, but don’t. Think about specific occasions, and specific behaviour, and point to exactly what the person did, and exactly how it made you feel. The more specific the better, as it is much easier to hear about a specific occasion than about ‘all the time’! 4. Feedback should be timely It’s no good telling someone about something that offended or pleased you six months later. Feedback needs to be timely, which means while everyone can still remember what happened. If you have feedback to give, then just get on and give it. That doesn’t mean without thought. You still need to think about what you’re going to say and how. 5. Pick your moment There are times when people are feeling open to feedback and times when they aren’t. This is where your awareness of the emotions and feelings of others is particularly important. This will help you to pick a suitable moment. For example, an angry person won’t want to accept feedback, even given skilfully. Wait until they’ve calmed down a bit. Feedback doesn’t just happen in formal feedback meetings. Every interaction is an opportunity for feedback, in both directions. Some of the most important feedback may happen casually in a quick interchange, for example, this one, overheard while two colleagues were making coffee: Becks (laughing): “You remind me of my mum.” Ella (her boss): “Really, why?” Becks: “She gets really snappy with me when she’s stressed too.” Ella: “Oh, I’m so sorry, have I been snapping at you? I am a bit stressed, but I’ll try not to do it in future. Thank you for telling me, and I’m sorry you needed to.” Becks had, quite casually, raised a serious behavioural issue with Ella. Ella realised that she was fortunate that Becks had recognised the behavioural pattern from a familial situation and drawn her own conclusions. However, Ella also recognised that not everyone she would ever work with would do the same. Having been made aware of her behaviour, she chose to change it. Becks had also, casually or not, given feedback in line with all the rules: it was about Ella’s recent behaviour, and so was specific and timely, and showed how Becks perceived it. It was also at a good moment when Ella was relaxed and open to discussion. Receiving Feedback It’s also important to think about what skills you need to receive feedback, especially when it is something you don’t want to hear, and not least because not everyone is skilled at giving feedback. Be Open to the Feedback In order to hear feedback, you need to listen to it. Don’t think about what you’re going to say in reply, just listen. And notice the non-verbal communication as well, and listen to what your colleague is not saying, as well as what they are. Ensure that you have fully understood all the nuances of what the other person is saying and avoid misunderstandings. Use different types of questions to clarify the situation, and reflect back your understanding, including emotions. For example, you might say: “So when you said …, would it be fair to say that you meant … and felt …?” “Have I understood correctly that when I did …, you felt …?” Make sure that your reflection and questions focus on behaviour, and not personality. Even if the feedback has been given at another level, you can always return the conversation to the behavioural, and help the person giving feedback to focus on that level. Emotional Intelligence is essential. You need to be aware of your emotions (self-awareness) and also be able to manage them (self-control), so that even if the feedback causes an emotional response, you can control it. And finally… Always thank the person who has given you the feedback. They have already seen that you have listened and understood, now accept it. Acceptance in this way does not mean that you need to act on it. However, you do then need to consider the feedback, and decide how, if at all, you wish to act upon it. That is entirely up to you, but remember that the person giving the feedback felt strongly enough to bother mentioning it to you. Do them the courtesy of at least giving the matter some consideration. If nothing else, with negative feedback, you want to know how not to generate that response again. Behaviour Feedback Of course, there are many feedback models and theories but a really useful and simple model is the AID Feedback Model. The AID model is great for delivering behaviour feedback. AID provides a useful tool for people to structure their feedback or coaching conversation and dialogue around in order to ensure that they are constructively managing how they deliver the feedback – so that the recipient is clear and capable of taking the right action or next step. A Action The person giving the feedback specifically defines the observable action or behaviours that the individual has taken which is either positive or negative. Very importantly and as highlighted here, the action must be observable – in other words, it must be based on actions / behaviours that can be defined and that have been observed by others. You can use things you have seen, heard or felt. One example could be “Over the last two weeks, you’ve signed in for work late on 6 occasions”/ This would be better and less subjective than “You’re building a track record for lateness now, you’re constantly late these days”. Another example could be “I noticed that you refused to respond to Maya three times in the team meeting.” rather than “You seemed pretty rude to Maya in the meeting.” I Impact Here the person presenting the feedback must explain the impact of the action not only for the individuals involved but for the greater ecology i.e. self – team – organisation – industry reputation etc. An example of using Impact within the AID model would be “the impact of this is that key tasks cannot be started until your input is complete. The impact of this is that there is a delay in the department projects for the overall team, specifically connected to your lateness” This would be better than “the impact of this is that everyone is feeling frustrated and is fed up with you.” D Do Lastly, this where the giver of the feedback outlines the behaviour that they would like the person to Do in the future such as continuing or changed behaviour for the future. An example of Do could be “From now, I do expect to see your work attendance without any lateness and if you think you are going to be late, I expect you to call me directly at least 30 minutes before you’re due in. So, can we just clarify, what is it you must do to improve in moving forward.” In a coaching or mentoring context “Tell me what you should now do about this?” rather than “So don’t let it happen again” Of course, this part of AID with Do is easier if the person reports to you. It’s not so easy if it’s a peer or a manager. Perhaps the use of ‘we’ could help here. An example being “So what should we do about it if it happens again to help improve things?” This is just a short introduction to the AID model, the real challenge comes when we are engaging in a dialogue of feedback delivery – we often need to engage coaching and listening skills to really influence behavioural change. Alec McPhedran Chtd Fellow CIPD, Chtd Mngr CMI, MAC, MCMI is a people skills development specialist. This is typically done through one to one coaching, facilitated learning, media training and team development. Visit www.mcphedran.co.uk Copyright © Alec McPhedran 2024

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorAlec McPhedran is a long established creative sector trainer, coach and mentor. Archives

April 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed