|

Giving and Recieving Feedback2/8/2023

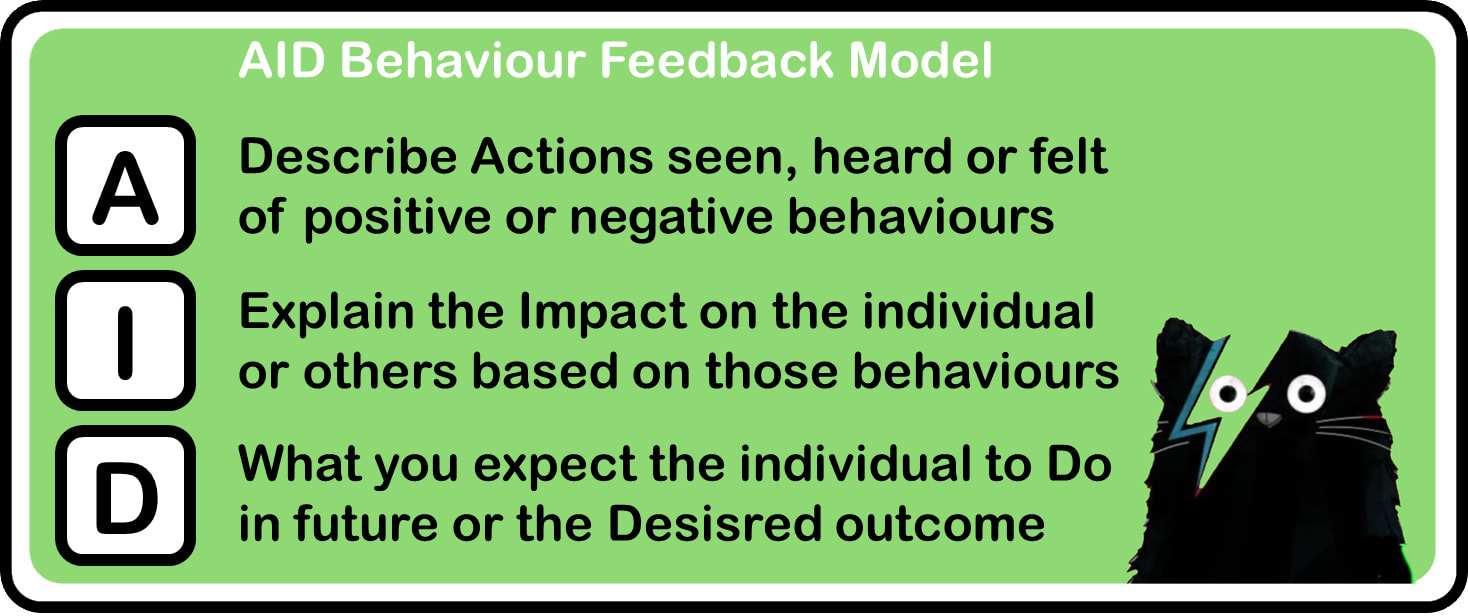

0 Comments Giving and Receiving Feedback Giving and receiving feedback is an essential skill in both personal and professional relationships. Constructive feedback can lead to growth, improved performance, and better relationships when delivered and received effectively. Here, Alec McPhedran gives an overview of approaches to giving and receiving feedback. In life as much as in work, it’s important to know how to provide feedback to others, effectively and constructively without causing offence. Equally, and often less considered, is the ability to seek and receive feedback. There are many opportunities in life for providing others with and for receiving feedback, from commenting on the way that your colleague has carried out a task, to discussing your behaviour with them. This item focuses on the process of communicating with someone about something that they have done or said, with a view to changing or encouraging that behaviour. This is often called ‘giving feedback’, and when you do, you want your feedback to be effective. 'Feedback' is a frequently used term in communication theory. It is worth noting that this page is not about what might loosely be called ‘encouragement feedback’—the ‘yes I’m listening’-type nods and ‘uh-huhs’ which you use to tell someone that you are listening. What is Effective Feedback? For our purposes, we will define effective feedback as that which is clearly heard, understood and accepted. Those are the areas that are within your power. You have no control over whether the recipient chooses to act upon your feedback, so let’s put that to one side. So how can you make sure that your feedback is effective? Develop your feedback skills by using these few rules, and you’ll soon find that you’re much more effective. 1. Feedback should be about behaviour not personality The first, and probably the most important rule of feedback is to remember that you are making no comment on what type of person they are, or what they believe or value. You are only commenting on how they behaved. Do not be tempted to discuss aspects of personality, intelligence or anything else. Only behaviour. 2. Feedback should describe the effect of the person’s behaviour on you After all, you do not know the effect on anyone or anything else. You only know how it made you feel or what you thought. Presenting feedback as your opinion makes it much easier for the recipient to hear and accept it, even if you are giving negative feedback. After all, they have no control over how you felt, any more than you have any control over their intention. This approach is a blame-free one, which is therefore much more acceptable. Choose your feedback language carefully. Useful phrases for giving feedback include: “When you did [x], I felt [y].” “I noticed that when you said [x], it made me feel [y].” “I really liked the way that you did [x] and particularly [y] about it.” “It made me feel really [x] to hear you say [y] in that way.” 3. Feedback should be as specific as possible Especially when things are not going well, we all know that it’s tempting to start from the point of view of ‘everything you do is rubbish’, but don’t. Think about specific occasions, and specific behaviour, and point to exactly what the person did, and exactly how it made you feel. The more specific the better, as it is much easier to hear about a specific occasion than about ‘all the time’! 4. Feedback should be timely It’s no good telling someone about something that offended or pleased you six months later. Feedback needs to be timely, which means while everyone can still remember what happened. If you have feedback to give, then just get on and give it. That doesn’t mean without thought. You still need to think about what you’re going to say and how. 5. Pick your moment There are times when people are feeling open to feedback and times when they aren’t. This is where your awareness of the emotions and feelings of others is particularly important. This will help you to pick a suitable moment. For example, an angry person won’t want to accept feedback, even given skilfully. Wait until they’ve calmed down a bit. Feedback doesn’t just happen in formal feedback meetings. Every interaction is an opportunity for feedback, in both directions. Some of the most important feedback may happen casually in a quick interchange, for example, this one, overheard while two colleagues were making coffee: Becks (laughing): “You remind me of my mum.” Ella (her boss): “Really, why?” Becks: “She gets really snappy with me when she’s stressed too.” Ella: “Oh, I’m so sorry, have I been snapping at you? I am a bit stressed, but I’ll try not to do it in future. Thank you for telling me, and I’m sorry you needed to.” Becks had, quite casually, raised a serious behavioural issue with Ella. Ella realised that she was fortunate that Becks had recognised the behavioural pattern from a familial situation and drawn her own conclusions. However, Ella also recognised that not everyone she would ever work with would do the same. Having been made aware of her behaviour, she chose to change it. Becks had also, casually or not, given feedback in line with all the rules: it was about Ella’s recent behaviour, and so was specific and timely, and showed how Becks perceived it. It was also at a good moment when Ella was relaxed and open to discussion. Receiving Feedback It’s also important to think about what skills you need to receive feedback, especially when it is something you don’t want to hear, and not least because not everyone is skilled at giving feedback. Be Open to the Feedback In order to hear feedback, you need to listen to it. Don’t think about what you’re going to say in reply, just listen. And notice the non-verbal communication as well, and listen to what your colleague is not saying, as well as what they are. Ensure that you have fully understood all the nuances of what the other person is saying and avoid misunderstandings. Use different types of questions to clarify the situation, and reflect back your understanding, including emotions. For example, you might say: “So when you said …, would it be fair to say that you meant … and felt …?” “Have I understood correctly that when I did …, you felt …?” Make sure that your reflection and questions focus on behaviour, and not personality. Even if the feedback has been given at another level, you can always return the conversation to the behavioural, and help the person giving feedback to focus on that level. Emotional Intelligence is essential. You need to be aware of your emotions (self-awareness) and also be able to manage them (self-control), so that even if the feedback causes an emotional response, you can control it. And finally… Always thank the person who has given you the feedback. They have already seen that you have listened and understood, now accept it. Acceptance in this way does not mean that you need to act on it. However, you do then need to consider the feedback, and decide how, if at all, you wish to act upon it. That is entirely up to you, but remember that the person giving the feedback felt strongly enough to bother mentioning it to you. Do them the courtesy of at least giving the matter some consideration. If nothing else, with negative feedback, you want to know how not to generate that response again. Behaviour Feedback Of course, there are many feedback models and theories but a really useful and simple model is the AID Feedback Model. The AID model is great for delivering behaviour feedback. AID provides a useful tool for people to structure their feedback or coaching conversation and dialogue around in order to ensure that they are constructively managing how they deliver the feedback – so that the recipient is clear and capable of taking the right action or next step. A Action The person giving the feedback specifically defines the observable action or behaviours that the individual has taken which is either positive or negative. Very importantly and as highlighted here, the action must be observable – in other words, it must be based on actions / behaviours that can be defined and that have been observed by others. You can use things you have seen, heard or felt. One example could be “Over the last two weeks, you’ve signed in for work late on 6 occasions”/ This would be better and less subjective than “You’re building a track record for lateness now, you’re constantly late these days”. Another example could be “I noticed that you refused to respond to Maya three times in the team meeting.” rather than “You seemed pretty rude to Maya in the meeting.” I Impact Here the person presenting the feedback must explain the impact of the action not only for the individuals involved but for the greater ecology i.e. self – team – organisation – industry reputation etc. An example of using Impact within the AID model would be “the impact of this is that key tasks cannot be started until your input is complete. The impact of this is that there is a delay in the department projects for the overall team, specifically connected to your lateness” This would be better than “the impact of this is that everyone is feeling frustrated and is fed up with you.” D Do Lastly, this where the giver of the feedback outlines the behaviour that they would like the person to Do in the future such as continuing or changed behaviour for the future. An example of Do could be “From now, I do expect to see your work attendance without any lateness and if you think you are going to be late, I expect you to call me directly at least 30 minutes before you’re due in. So, can we just clarify, what is it you must do to improve in moving forward.” In a coaching or mentoring context “Tell me what you should now do about this?” rather than “So don’t let it happen again” Of course, this part of AID with Do is easier if the person reports to you. It’s not so easy if it’s a peer or a manager. Perhaps the use of ‘we’ could help here. An example being “So what should we do about it if it happens again to help improve things?” This is just a short introduction to the AID model, the real challenge comes when we are engaging in a dialogue of feedback delivery – we often need to engage coaching and listening skills to really influence behavioural change. Alec McPhedran Chtd Fellow CIPD, Chtd Mngr CMI, MAC, MCMI is a people skills development specialist. This is typically done through one to one coaching, facilitated learning, media training and team development. Visit www.mcphedran.co.uk Copyright © Alec McPhedran 2024

0 Comments

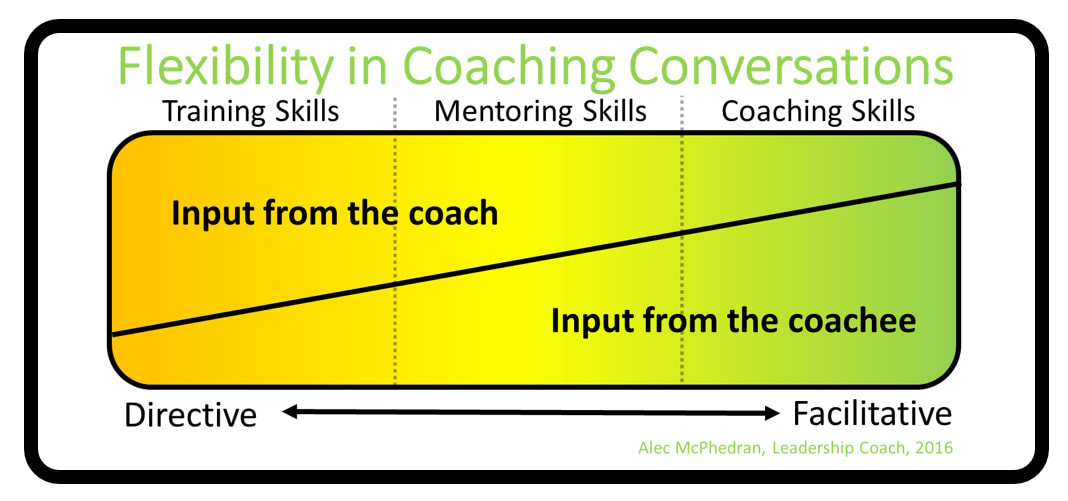

The Coaching Conversation Model is a tool to explain the way a coaching conversation may at times flex into training, teaching or mentoring mode as well as working towards the ideal coaching approach. Here leading creative sector coach Alec explains the model to help new coaches appreciate the skill in flexing coaching conversations.

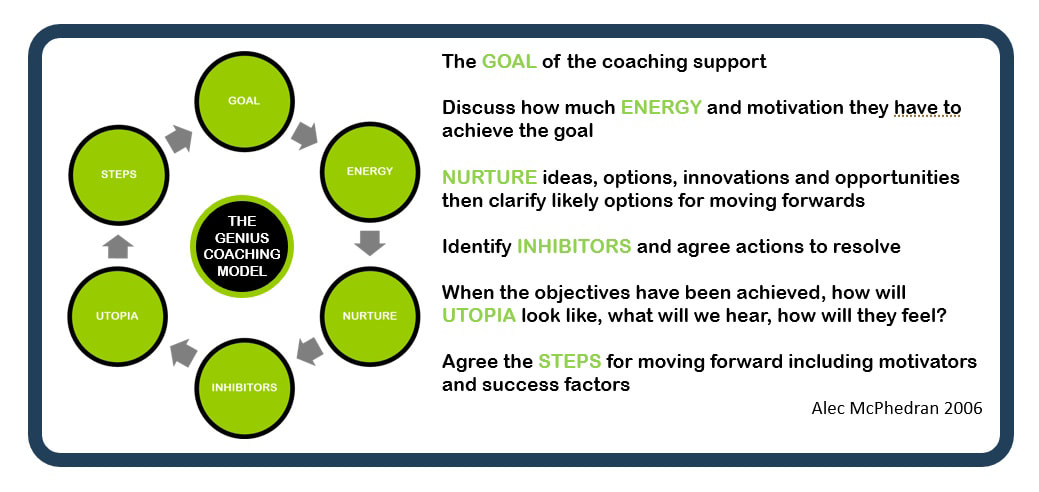

When I was being trained to become a coach, much of the advice was to mainly use open-ended questions such as who, what, why, where, when and how. Equally to make use of TED, tell me about, explain to me or describe to me, which are of course powerful open-ended questions. The aim therefore was to ensure that I the coach contributed very little by way of advice or influence to the coachee and that the answer sits within them. This of course is true in one sense. Indeed, that would be the perfect coaching session – I ask profound questions, the you answer them, sort yourself out, you leave happy and I send my invoice. What a life. As we develop out coaching understanding, we recognise that the perfect approach to coaching conversation doesn’t always happen. Sometimes we need to use and trust our experience and step back a bit into training mode to explain a concept and then return to coaching on how they can use that concept to develop their ideas. We may well also throw in some personal experience by way of example, which in turn means I may well be in mentoring mode. To me coaching is facilitating the learning of others to help them reach their unique potential. So, if part of coaching is facilitating, then we need to be able to flex and react accordingly for the benefit of the coachee. When I deliver workshops on coaching to managers, the sessions on managing coaching conversations can come over a bit contradictory or confusing. On that basis, and being a visual type, I developed the Coaching Conversation Model as a discussion tool to explore the range of approaches to coaching conversations. This has evolved over a number of years but what is great about the model is that it helps to initiate valuable discussions on the flexibility needed in coaching conversations. Directive to Facilitative Coaching The more we instruct or influence the conversation, the less the coachee contributes to the conversation. That is directive coaching. If for example, I am trying to help a manager work through giving feedback on a colleague’s behaviour, I tend to see how they would approach it and what the likely outcomes would be based on that approach. If we agreed that it might not be the most appropriate approach or the manager was not familiar with feedback theory, I could offer some ideas on feedback theory to help move the situation forward. A typical model I use, because of its simplicity and usefulness, is the AID feedback model. That is A for action or actions I have seen, heard or felt. I is for the impact of those actions and the likely consequences and D for what should they do about it in the future. On that basis, I am in training or teaching mode using my training skills. Once I have put the theory across, we then move back to a coaching approach by getting back to asking them how they could use that model in that particular situation. I am back to facilitating the thinking of the coachee, not contributing ideas but simply coaching. That is facilitative coaching – the main conversation coming from the coachee. Much of this approach has strong links to Heron’s Six Categories of Intervention (1975, in Hawkins & Smith, 2006) offering approaches from an authoritative set of interventions to facilitative interventions. Heron’s models confirm that as a coach, we need to flex our approach as we work with our coachees. Development Through Coaching A frequent misunderstanding I find when coaching managers is their understanding of development. Many people feel that development means training. To me, development is how do we give people new knowledge, skills and behaviours. This widens our options with development opportunities such as coaching, mentoring, teaching, shadowing, secondment and so on. Training may or may not be a part of development. In developing the Coaching Conversations model, and for the sake of simplicity, I have used training, coaching and mentoring by way of example. You can use whatever is appropriate to your learning group with headings such as educating, teaching, facilitating and so on. For me, the basics of training, coaching and mentoring work well. As an introduction to discussing coaching conversations, I run an activity in which the group is normally split in to three. Each group is allocated either training, coaching or mentoring. They then write words on a Post-It that reflects clearly their development option. They then select the top three words and create a simple sentence defining training, coaching or mentoring. During feedback and discussion, we then evolve their work in a way that explains each and differentiates the three. Before the session, they are encouraged to bring along a preferred description on coaching and mentoring. We all have our view on what each development option are but the point of the exercise is to understand those options and develop a way in which to explain them simply and clearly in a coaching session. The value of the exercise is that participants gain a better understanding of each and recognise the differences, especially between mentoring and coaching. I often support this with am anecdote that highlights those differences. From this we can then move on to discussing coaching conversations, and on my events, I tend to use training, coaching and mentoring. To keep it simple, I use the following explanations for training, coaching and mentoring: Training In training mode, we instruct, we tell. Much of the input to the conversation is from the coach. It is explaining ideas, concepts or theories. Coaching When we coach, we facilitate, we ask. This is where the coach concentrates on the objective of the coaching session – be it coachee or jointly identified. This uses questioning, active listening, feedback, problem solving, idea generation and summarising skills to guide the coachee. It’s asking rather than telling. It allows the coachee to develop their thinking capability and self-belief in their capability. The main input on the conversation is ideally from the coachee. Coaching is facilitating the learning of others to help them reach their unique potential. Mentoring A mentor is a more experienced or senior person who offers guidance, support, pastoral care, challenge or wisdom to another in developing them as a person. This is where the coach applies their mentoring skills, jointly contributes to the conversation with the coachee. The mentoring approach allows the coach to offer ideas from their experiences, points out ideas in an appropriate direction and guides based on their wisdom. I’m conscious that my definitions of training, coaching and mentoring will not sit well with others. In fact, when I search on a web browser for ‘definition of coaching’, it tells me if has found 331,000,000 results with thousands of definitions and interpretations of definitions. We all have our own views, beliefs and versions of each based on our unique experiences. The key thing is you have a description in which you feel is right and it helps to explain what it is to a coachee, yet it is simple and easy to understand. I also feel it must clearly differentiate between the three development approaches. The Coaching Conversation Model The purpose of the coaching conversation model is to help a new coach understand that the conversation will flex in to the territory of teaching, training, education or mentoring but with the aim of making sure we focus on and always returning to the coaching approach where appropriate. A pure coaching session is the Utopia but in many cases I have experienced, we do have to flex for the benefit of the coachee and the coaching session or programme goal. The Coaching Conversation Model has been developed by Alec McPhedran Fellow CIPD, Chtd Mngr CMI, MAC, MCMI as a tool for people who coach; to help understand the conversation management of a coaching session. Alec is a trainer, coach and mentor. He specialises in one to one coaching, facilitated learning, media training and team development. He developed the GENIUS Coaching Model, a guide to managing the flow of a coaching conversation. For further information visit www.mcphedran.co.uk Copyright © Alec McPhedran 2024 Coaching is facilitating people to reach their unique potential. A coach should consider the effective management of the coaching process to reach session goals as effectively and as focused as possible. Alec McPhedran explains the simple to use but highly effective GENIUS coaching framework for creative talent coaching sessions. In essence, coaching is a simple process. However, we must make sure we do simple well. At its heart lies good questioning, listening and the ability to summarise. The challenges are building trust and maintaining a positive working and open relationship in which the coachee feels they are the focus of attention and that they are being helped to work on their ideas. The additional skill is managing the process of the coaching session. This has to be timely as well as facilitating the individual to move forward. In the creative industries in which I mainly work, it is critical ideas and solutions came from the individual being coached. That’s really hard when you believe you know what the solution is. But surely that’s one of the issues of coaching, “What you believe the solution is.” Great coaching is about working the individual. It’s their imagination and their aspiration. Our job is to help turn these into a reality. Not the coach’s reality or perceived reality. It has to be owned by the coachee. As a coach, your inputs have to be really relevant, valid and appropriate if and when invited to do so. You, the coach, act as the conductor. The individual has the talent. The coach’s role is to get the best out of the talent. Like most coaches, I have come across a number of really useful coaching models, including the simple but highly effective GROW model. The common view is that the GROW model derived from Performance Coaching by John Whitmore. GROW is used to structure the coaching session; Goals, Realities, Options and Will, as in “What will you do?” This is pretty good, particularly for offering line managers a coaching tool but for professional coaches it sometimes might need a bit more. Another useful model is CLEAR, developed by Peter Hawkins. CLEAR concentrates on Contracting, Listening, Exploring, Action and Review. Working in the creative industries often has me having to work with additional technique in the coaching session. Creativity, innovation, exciting aspirations and ideas that need turning into a reality. That’s the amazing and exciting challenge in media with creative coaching. For me, a new approach was needed to help inspire and push my clients. GENIUS GENIUS coaching developed following a chat with a pretty cynical script-writing friend. She felt coaching had its place but most definitely not in the world of ‘creative people’. Her previous experience of being coached while working at a leading broadcaster had been helpful but only in career progression and not on her desire to be the best in her field of telling stories. A number of coaches had not been able to really meet her creative aspiration. This made me think about myself, my own ability to go further than I had been before with people and therefore how could I meet her challenge? Yes there are excellent coaches who are very focussed on pushing people but are we held back with the SMART objective format? Are we sometimes held back by our own feelings if moving out of our own comfort level? Her point was do we really push people past their boundaries? Was I really helping by agreeing to a coachees initial objectives or was I really stretching them, taking them to new and exciting places, sometimes scary, in their ambition? Over the following months I revisited my coaching sessions, the processes I was using and depending on subjects, the results we were getting. Goals were being achieved but I was wondering could it have been wider reaching, more challenging – truly daring to be different. The GENIUS model of coaching evolved after testing it out on some knowing victims with mixed success. I was particularly influenced by Jenny Rogers, author of Coaching Skills, a Handbook. Jenny mixes coaching fantastically well with Neuro Linguistic Programming. Thinking of end goals, care with use of language and testing the energy to achieve things. People who were really up for a new adventure opened their mind to great new ideas, concepts and opportunities that truly seemed off the wall. But importantly, motivational for a creative person. With some, it made them feel uncomfortable and my learning was that you had to work with the aspiration and the reality of their ambition in their style. Again, not my ambition or my preferred coaching or creative thinking techniques. Eventually the GENIUS model came out, probably the result of a fire, aim ready strategy. It’s now one of my favourite models, particularly when working with exciting creative talent. GENIUS coaching is simple. GENIUS is a guide to running a coaching session. It’s yet another useful model for coaches for their toolkit. It does draw its inspiration from the likes of GROW, OSKAR and other coaching models. Simple is good but the skills is in doing simple well. Goals The first step of GENIUS is to set the GOALS, a rather obvious starting point. We know the goal, purpose or aim is critical for a number of reasons but primarily it provides us with the reminder of what it is we are working on, what needs to be achieved. It makes sure all future conversation is relevant to achieving the goal. With GENIUS coaching, there are three types of goals to set.

By using this three step approach to goal setting, it provides the coachee with consistency and focus for making things happen and with a clear understanding of why they need to do things. The key skill for the coach is managing and setting the aspirational goal. Energy Once the aspirational goal and the session goal (or goals) has been set, the next part of GENIUS coaching is to look at the ENERGY of the coachee. They may want to achieve something that is far reaching for them but do they really have the energy? The desire to achieve and the energy to do something can sometimes be poles apart. Get the client to rate their energy levels to make this work, perhaps by giving a score out of 10. Without the genuine energy to achieve the goal, is the goal the right one in the first place? Another useful tool to use here, again thanks to Jenny Rogers, is to ask how motivated they are about achieving the goals. A rating of 1 to 10 equally helps give some indication of possible investigation. A useful read on the importance of personal energy is the high performance pyramid by Jim Loehr and Tony Schwartz (2003). The focus of the model is the importance and connectivity in the four energy levels: physical, emotional, mental and spiritual. The theme is not so much about how you manage your time but how you manage (and control) your personal energy. Really helpful in probing commitment to achieving an aspiration. Nurture Once goals have been established and the energy levels checked to achieve them, you then need to NURTURE the range of opportunities and options. This is very much the Options stage of GROW. This again is where the questioning, listening, summarising and creative thinking skills of the coach come into play. Your ability to brainstorm, encourage creative thinking; thinking of things that are really off the wall, never been done before are absolutely critical. When nurturing ideas, this ideally should be treated in the same way as a pure brainstorming session. Pull out the ideas, don’t critique to early, set the parameters linked to the objectives and work through some of the ideas. This is also a great time to use challenging and creative thinking tools such as de Bono’s Six Thinking Hats (data, emotion, negativity, positiveness, feel good, innovative thinking and process). Once you have looked at each idea, work through and prioritise the key actions that came out of the nurturing process. Priority action one is the way forward. Options two, three and four – potential back up ideas. From the Six Thinking Hats model you will then be able to move into the next stage of GENIUS coaching thanks to the identifying emotions and negatives from the red and black hat discussions. Inhibitors That’s because you need to revisit the agreed priority actions from the nurturing stage and identify the INHIBITORS. That is, what is going to stop the ideas from working? This is really powerful as you seek out the negatives. It’s those negatives that you then address with the client to establish how they will be tackled should they arise. I guess the development of the cunning Plan B scenario. We are great at planning the perfect life with Plan A. Unfortunately life’s not perfect. Therefore it makes sense to anticipate inhibitors. Manage them into positives. It’s worthwhile at this point revisiting your nurtured actions to see if they need revising to reflect the points identified in the inhibitors stage of the session. Utopia So, we now know what we want, how much energy the client has to achieve their goal, we’ve generated some great ideas and have identified the potential problems and the likely responses. If all works fantastically well then… UTOPIA; an imagined perfect place or state of things. This is where the coaches Neuro Linguistic Programming knowledge comes more into play. Can you get the individual to visually, auditory and kinaesthetically imagine their Utopia once the goals will be achieved? This is a powerful tool to make the end result of a coaching session feel real. It’s what turns that aspiration into the reality. Visioning, recording or feeling that end goal gives the goal life. It puts Utopia in the mind of the individual. I have even gone so far as to encourage clients to make that picture real – getting or drawing a close or true to life image and then placing it in eye sight at their desk. Weird I know but it definitely works. For the auditory types, a written statement always at hand seems to have the same effect. We’re back to the immense importance of goals. Once they look and feel real, once we are emotionally attached to them, they will become real. Developing, writing down and imagining goals is an essential role of the coach to get the client to understand this. Steps Finally, the coaching session is rounded off by summarising the STEPS to be taken by the coachee. What will they do between now and the next session? These are developed by writing SMART (specific, measurable, realistic, agreed and timed) Action Goals and clarifying the actual steps to take to achieve the Action Goals. I guess in the good old day that was called action planning. So there you have it. Yet another wonderful tool for coaching. The very simple GENIUS coaching model. It’s about pushing ambition and creativity further for creative people, exploring amazing and varied opportunities and imagining the realities of what success will look, feel or sound like. Obviously I know this model may not be perfect for some, that’s the beauty of the business we’re in. If we were all perfect then we wouldn’t have anybody to coach. The GENIUS Coaching Model G – Goals to be achieved E – Energy to achieve the goals N – Nurturing and exploring options to achieve the goals I – Inhibitors that may arise on the way to achieving goals U – Utopia when the goals will be achieved S – Steps to be taken to achieve the goals GENIUS coaching has been developed by Alec McPhedran Chard FCIPD, Chtd Mngr CMI, MAC, MCMI, as a tool for people who coach; to guide them through an inspirational and wide reaching coaching session for talented creative people. Alec is trainer, coach and mentor in the creative sector. For further information visit www.mcphedran.co.uk An Overview of the Pareto Principle

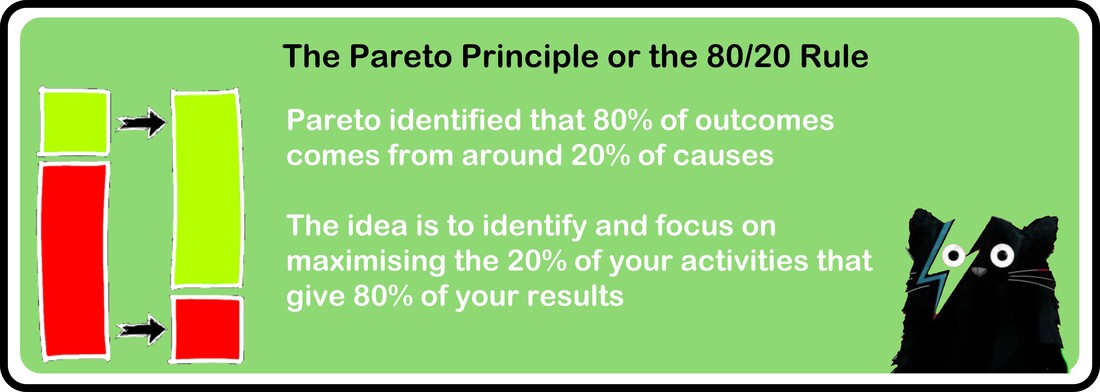

Do you know what contributes to your successes or your results? If you do know, how well therefore do you plan and prioritise those as key actions to be completed or areas to focus on? Understanding the Pareto Principle is a great planning tool to help you focus on the important things. Here, creative sector coach and trainer Alec McPhedran shares his thoughts on the Pareto Principle. The Pareto Principle, also known as the 80/20 rule or the law of the vital few, states that roughly 80% of the effects or results come from 20% of the causes or inputs. This principle is named after the Italian economist Vilfredo Pareto, who observed in 1895 that approximately 80% of Italy's land was owned by 20% of the population. Since Pareto’s findings, academics have applied Pareto’s 80/20 rule of cause and effect, also known as the Pareto principle, to a variety of situations outside of wealth distribution, including business principles, planning and professional development. It highlights the imbalanced distribution of outcomes, suggesting that a significant majority of the outcomes are driven by a relatively small portion of the inputs. For example, in business, the Pareto Principle implies that roughly 80% of a company's profits come from 20% of its customers, services or products. In project management, it suggests that 80% of the project's results are achieved through 20% of the effort and resources invested. In personal productivity, it implies that 80% of your results come from 20% of activities or tasks. It's important to note that the specific ratio of 80/20 is not always exact and can vary. It serves as a general guideline rather than a rigid rule. The key insight is that a small portion of the causes or inputs have a disproportionately significant impact on the outcomes. Specific highlights are: The 80/20 rule is a statistical rule that states that 80% of outcomes result from 20% of causes The 80/20 rule can help determine how to best allocate time, money, effort or resources When using the 80/20 rule, people try to prioritise the 20% of activity that give the greatest results Examples of the 80/20 Rule

By recognising and applying the Pareto Principle, individuals and organizations can focus their efforts and resources on the critical few aspects that generate the majority of the desired results. This approach allows for more efficient allocation of time, energy, and resources, leading to increased productivity and effectiveness. How do I use the Pareto Principle? To effectively use the Pareto Principle, also known as the 80/20 rule, in your personal or professional life, you could follow these steps: Identify the key factors: Start by identifying the areas or factors where the Pareto Principle is likely to apply. This could be in terms of tasks, customers, products, time, or any other relevant aspect that influences your outcomes Analyse the data: Collect data or information related to these factors. This could involve examining sales figures, customer data, project metrics, or any other relevant data source. Analyse the data to identify patterns or trends Apply the 80/20 analysis: Apply the Pareto Principle by identifying the vital few. Determine the factors or inputs that contribute the most to the desired outcomes. Look for the 20% of causes that drive 80% of the effects. For example, if you're analysing customer data, identify the top 20% of customers who generate 80% of your revenue Focus on the vital few: Once you have identified the critical factors, concentrate your efforts, resources, and attention on them. Allocate your time, energy, and resources in a way that maximizes the impact of the vital few. This could mean prioritizing your high-value customers, focusing on your most profitable products, or streamlining processes that contribute the most to your goals Streamline or eliminate the trivial many: The Pareto Principle also highlights that a large portion of the causes or inputs may have a minimal impact on the outcomes. Identify the trivial many, the 80% of causes that contribute only 20% of the effects, and evaluate whether they are worth the investment. Streamline or eliminate nonessential tasks, customers, products, or processes that don't significantly contribute to your desired results Regularly review and adapt: The Pareto Principle is not a one-time analysis but an ongoing process. Continuously monitor and review your data, outcomes, and resource allocation to ensure you are still focusing on the vital few. Market conditions, priorities, and other factors may change over time, so regularly reassess and adapt your strategies accordingly By applying the Pareto Principle, you can optimize your efforts, resources, and decision-making to achieve more significant results with less wasted time and resources. Alec McPhedran Chtd Fellow CIPD, Chtd Mngr CMI, MAC, MCMI is a creative coach, mentor and trainer. He specialises in one to one coaching, facilitated learning, media training and career coaching. For further information, contact Alec at www.mcphedran.co.uk. Copyright © Alec McPhedran 2024 Approaches to Conflict Management

Conflict management refers to the process of handling and resolving conflicts or disagreements that arise between individuals, groups, or organizations. It involves a range of strategies and techniques aimed at addressing the underlying issues, reducing tension, and reaching a mutually acceptable resolution. Here, creative sector coach and trainer Alec McPhedran shares his thoughts on conflict management and some approaches. Conflict can arise due to differences in opinions, values, goals, or interests. It can occur in various settings, including personal relationships, workplaces, communities, and international relations. Conflict management is crucial because unresolved conflicts can lead to negative consequences such as strained relationships, decreased productivity, or even aggression. Conflict management refers to the approaches in handling conflicts and disagreements effectively to achieve resolution and maintain positive relationships. There are several approaches and strategies that can be used to manage conflicts. Here are some common approaches to conflict management: Collaboration: This approach focuses on finding a win-win solution by involving all parties in the conflict. It encourages open communication, active listening, and brainstorming to identify common interests and create a solution that satisfies everyone's needs Compromise: In this approach, both parties involved in the conflict make concessions and reach a middle ground. Each party gives up some of their demands to achieve a mutually acceptable outcome. Compromise requires negotiation and finding areas of agreement while acknowledging and accepting differences Accommodation: This approach involves satisfying the needs and interests of one party while disregarding or minimizing the concerns of the other. It may be used when maintaining harmony and preserving relationships is more important than achieving a specific outcome. Accommodation can be effective in situations where one party has more power or when the issue is of low importance Avoidance: Sometimes, conflicts can be managed by avoiding or postponing them. This approach may be used when the conflict is trivial, emotions are high, or when the timing is not right for a productive discussion. However, prolonged avoidance can lead to unresolved issues and may escalate the conflict in the long run Competition: In this approach, each party focuses on their own interests and aims to win the conflict. It can involve assertiveness, the use of power, and a disregard for the needs and concerns of the other party. While competition may be appropriate in certain situations, such as when quick decisions are required or when ethical issues are involved, it can strain relationships and lead to negative outcomes Mediation: Mediation involves the intervention of a neutral third party who facilitates communication and negotiation between the conflicting parties. The mediator helps to identify the underlying issues, improve understanding, and guide the parties towards a mutually agreeable solution. Mediation can be especially useful when emotions are high or when the parties are unable to resolve the conflict on their own Arbitration: Arbitration is a more formal approach where an impartial third party, called an arbitrator, reviews the conflict and makes a binding decision. This approach is often used when the parties are unable to reach an agreement or when the conflict involves legal matters. The arbitrator's decision is final and enforceable The choice of approach depends on the nature of the conflict, the goals of the parties involved, and the relationship dynamics. Effective conflict management involves selecting the most appropriate approach for each situation and ensuring that the process is fair, respectful, and leads to a satisfactory resolution. Alec McPhedran Chtd Fellow CIPD, Chtd Mngr CMI, MAC, MCMI is a creative coach, mentor and trainer. He specialises in one to one coaching, facilitated learning, media training and career coaching. For further information, contact Alec at www.mcphedran.co.uk. Copyright © Alec McPhedran 2024 An Introduction to Unconscious Bias from Alec McPhedran

Sometimes, we are not fully aware of our biases and in working with others, managing unconscious bias is a great skill that does need learning and constant checking in. Here, creative sector coach and trainer Alec McPhedran gives an overview of unconscious bias basis. Unconscious bias refers to the biases and prejudices that we hold at a subconscious level, often without our awareness or intention. These biases are influenced by our upbringing, socialization, cultural norms, and personal experiences. They can shape our attitudes, beliefs, and judgments about individuals or groups, leading to unfair or discriminatory treatment, even if we consciously strive to be unbiased. Unconscious biases can manifest in various forms, such as racial bias, gender bias, age bias, and more. They can affect our perceptions, decision-making, and behaviour, leading to unintended consequences and perpetuating inequalities. Importantly, unconscious biases are not limited to any specific group or individual; they can be present in anyone, regardless of their background or intentions. Understanding unconscious bias is essential because it helps us recognize and challenge our own biases, enabling us to make more fair and informed decisions. By becoming aware of these biases, we can actively work towards reducing their impact and promoting inclusivity and equality. It's important to note that unconscious bias does not make individuals inherently bad or prejudiced. Rather, it is a natural cognitive process that stems from the brain's attempt to simplify complex information and make quick judgments. However, when left unchecked, unconscious bias can perpetuate stereotypes, reinforce systemic inequalities, and hinder diversity and inclusion efforts? Addressing unconscious bias requires ongoing self-reflection, education, and a commitment to fostering an inclusive mindset. Organizations and individuals can implement strategies such as diversity training, diverse hiring practices, creating inclusive environments, and promoting awareness of bias to mitigate the impact of unconscious biases. Recognizing that unconscious biases exist and taking proactive steps to counteract them is crucial for promoting fairness, equality, and creating a more inclusive society where everyone has an equal opportunity to thrive. Types of Unconscious Bias There are several types of unconscious biases that can influence our perceptions and decision-making. Here are some common types: Implicit Bias: Implicit biases are automatic and unconscious biases that result from associations formed in our minds based on experiences, media, cultural influences, and stereotypes. These biases can affect our judgments and behaviour towards individuals or groups, even when we consciously reject stereotypes Affinity Bias: Affinity bias refers to the tendency to prefer and be more positively disposed towards people who are similar to ourselves in terms of background, interests, or experiences. This bias can lead to favouritism and exclusion of individuals who do not fit our personal "in-group.” Confirmation Bias: Confirmation bias is the tendency to seek, interpret, and remember information in a way that confirms our pre-existing beliefs or stereotypes. This bias can lead us to selectively notice or remember information that supports our views while ignoring or dismissing evidence that contradicts them Halo Effect: The halo effect occurs when we form an overall positive impression of a person based on a single positive trait or characteristic. For example, if someone is physically attractive, we may assume they are also intelligent, competent, or trustworthy, without objective evidence to support those assumptions Stereotyping: Stereotyping involves making generalizations or assumptions about individuals based on their membership in a particular group. Stereotypes are often based on societal or cultural beliefs and can lead to unfair judgments and treatment of individuals, perpetuating biases and discrimination In-group Bias: In-group bias is the tendency to favour individuals who belong to the same group as us, whether it's based on race, ethnicity, gender, nationality, or other factors. This bias can lead to exclusion or marginalization of individuals from different groups and hinder diversity and inclusion efforts Availability Bias: Availability bias refers to the tendency to rely on readily available information or examples that come to mind easily when making judgments or decisions. This bias can lead us to overestimate the prevalence or importance of certain events or traits based on their prominence in our personal experiences or the media Attribution Bias: Attribution bias involves making assumptions about the causes of someone's behaviour, often based on stereotypes or preconceived notions. For example, attributing a woman's success to luck or affirmative action rather than recognizing her skills and abilities. It's important to note that these biases are not exhaustive, and individuals can exhibit various combinations of biases. Recognizing and understanding these biases is the first step towards mitigating their impact and promoting fair and unbiased decision-making. Alec McPhedran Chtd Fellow CIPD, Chtd Mngr CMI, MAC, MCMI is a creative coach, mentor and trainer. He specialises in one to one coaching, facilitated learning, media training and career coaching. For further information, contact Alec at www.mcphedran.co.uk. Copyright © Alec McPhedran 2024 |

AuthorAlec McPhedran is a long established creative sector trainer, coach and mentor. Archives

April 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed